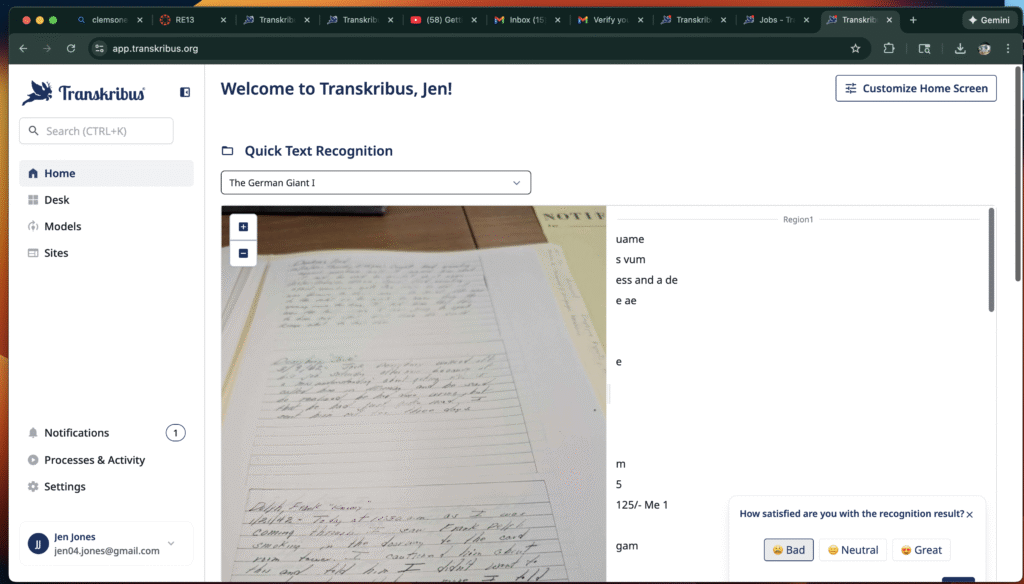

For this final research exercise, I had the chance to experiment with Transkribus, an AI-powered handwriting recognition tool designed to help scholars work with manuscript materials. I approached the platform with a mix of curiosity and skepticism, since most of my archival work involves handwritten incident reports and permits from mill towns in the American South. These documents are often written in highly stylized cursive, which can be difficult to decipher even for trained eyes.

The setup process was straightforward. After creating an account and selecting “Academic Research,” “Just Me,” and “A Small Collection,” I named my project and entered the workspace Transkribus calls “My Desk.” The interface was clean and intuitive, and I appreciated that the tutorials were short and accessible. Within minutes, I was uploading sample documents and testing the recognition features.

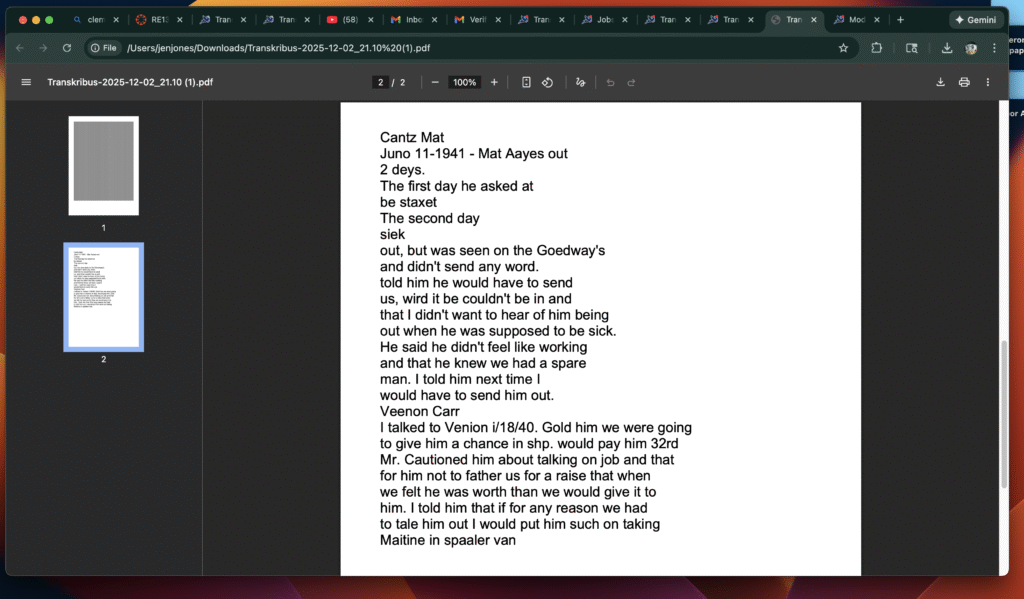

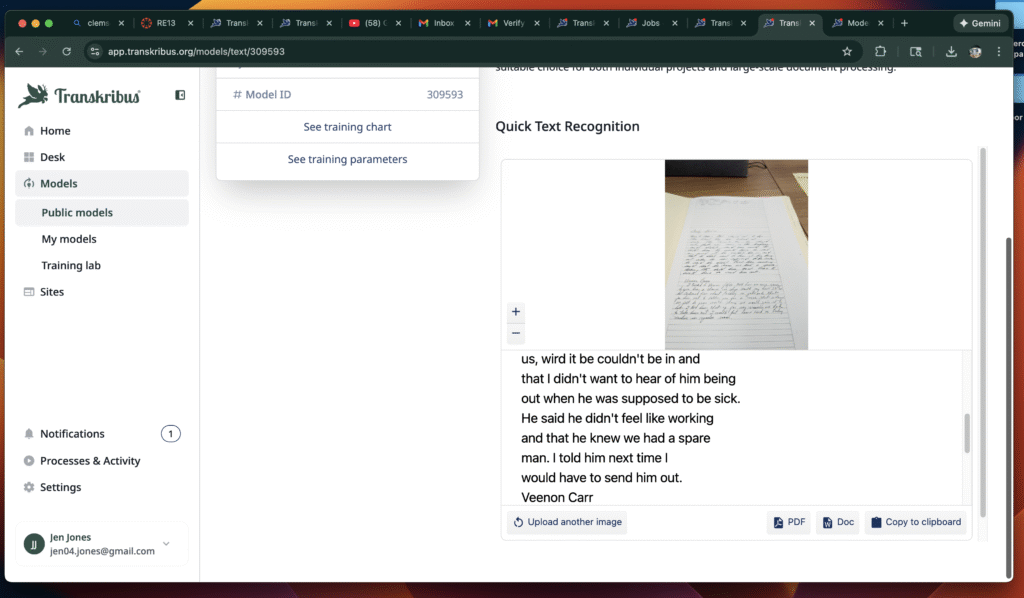

One of my first observations was that the software performed much better with typed or printed materials than with handwritten ones. When I uploaded a printed page, the transcription was nearly flawless, and the tool neatly separated the text into manageable sections. This alone is useful, since it makes digitized documents easier to read and annotate. However, when I tried the handwritten incident reports from Clifford Mill, the results were more uneven. The AI struggled with the flourishes and idiosyncrasies of the cursive script, often misreading words or leaving gaps.

That said, I can see enormous potential here. Transkribus allows users to train models on specific handwriting styles, meaning that with enough input, the system could eventually learn to recognize the quirks of the mill reports. Since I have pages and pages of these incident records, I could build a custom model over time. This would not only save me hours of manual transcription but also open up new possibilities for analysis. For example, once transcribed, the reports could be searched for recurring themes—such as the kinds of behaviors that were praised or condemned in mill communities. This would give a more vivid picture of everyday life, especially the tensions between workers and management.

Another feature I found helpful was the way Transkribus split documents into sections, making them easier to navigate. Even when the handwriting recognition was imperfect, the segmentation helped me focus on smaller portions of text. I also experimented with uploading screenshots of both printed and handwritten materials, which gave me a clear sense of the tool’s strengths and limitations.

At this stage, my collection is relatively small—approximately 5,000 words—but the platform’s scalability is encouraging. I can imagine expanding this into a larger project, where the AI gradually improves as it encounters more examples of the same handwriting. The idea of “training” the tool feels collaborative, almost like teaching a research assistant to recognize a particular scribe’s style.

In conclusion, while Transkribus is not yet a perfect solution for my handwritten mill reports, it is a simple, accessible, and promising tool. With time and training, it could become an indispensable part of my workflow, helping me unlock the voices hidden in these difficult manuscripts. For historians working with challenging handwriting, this tool offers a glimpse of how AI might transform archival research—making the past not only more legible but also more searchable and analyzable.

I thought creating a timeline with TimelineJS would be simple. I love timelines—they’re such powerful visual tools for showing how events connect over time. So when I decided to make one about the rise of Hitler, I figured it would be a quick project. Spoiler alert: it wasn’t.

First, I started with what I knew best: Excel. I filled out a spreadsheet with all the dates, headlines, and details I wanted. I even used the column titles that TimelineJS requires. Feeling confident, I tried to publish it. But nothing happened. No timeline—just a plain spreadsheet.

Then I realized TimelineJS doesn’t work directly with Excel. It needs a Google Sheets file published to the web. So I copied everything into the official TimelineJS template in Google Sheets, saved it, and grabbed the URL. I embedded that link in my blog post, expecting magic. Still nothing.

At this point, I was frustrated. I had the data, the template, and the link, but the timeline refused to appear. I know timelines can make history come alive, and I’m curious enough to keep trying—especially because I want to compare Hitler’s rise to Trump’s in two separate timelines. But for now, I’ve just got an embedded spreadsheet sitting in my post.

Hopefully, after asking some questions in class and getting a few tips, I’ll figure out what went wrong. Because I still believe timelines are worth the effort—they’re one of the best ways to visualize complex stories.

Below is a link that shows the preview of my timeline. I was unable to embed it into the blog post.

With more time, I could have improved my skills with this application. I plan to revisit and complete this project in the future.

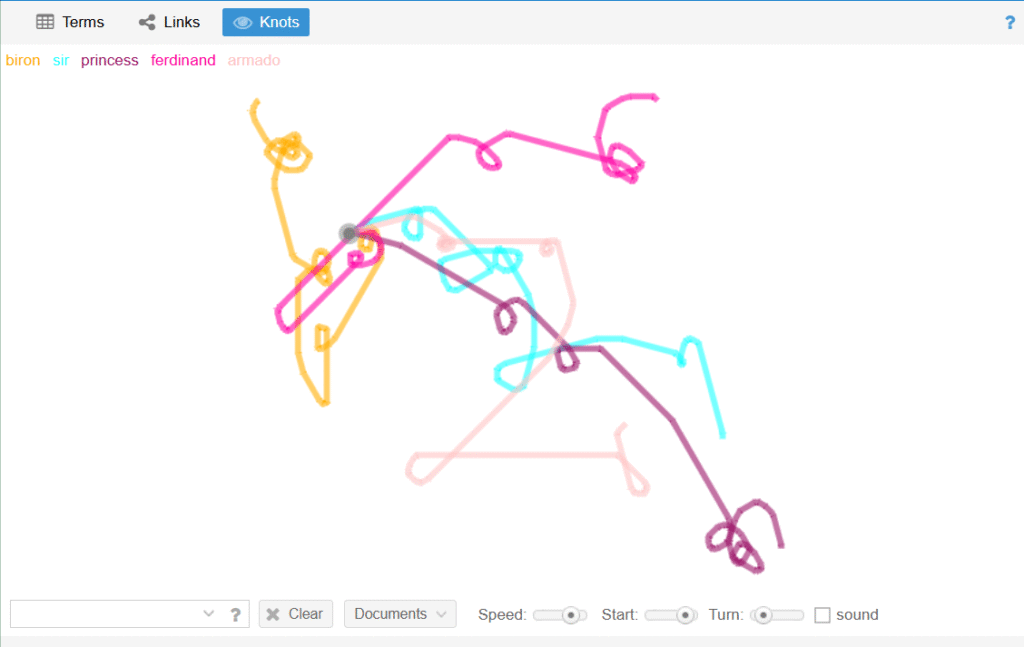

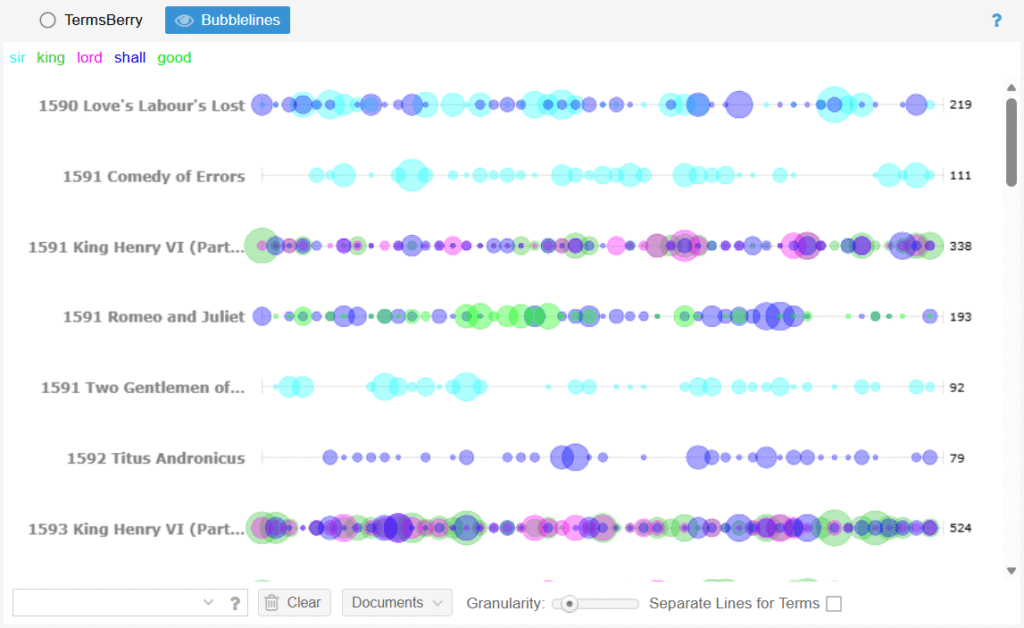

In my class, we have explored new tools, which was one of the most eye-opening experiences I’ve encountered. There are ways to create digital history without needing to be a coder. One of the most useful tools I’ve encountered is Voyant Tools—a web-based application for performing textual analysis on large corpora. For this class today, I explored Shakespeare’s plays using Voyant, and I quickly discovered how powerful and visually compelling this platform can be. For this exploration, I used the plays of Shakespeare.

Voyant Tools offers a preloaded corpus of Shakespeare’s plays, which can be accessed by clicking “Open” below the “Add texts” box. This corpus includes 895,737 words from 37 plays written between 1590–1613. You can also upload your own texts or use input boxes and URL links to compile texts from websites. The platform supports a wide range of file types—MS Word, Excel, HTML, RTF, PDF, XML, and Plain Text—making it incredibly flexible and user-friendly for researchers of all levels.

I was immediately drawn to two visual tools: Knots and Bubbles. Admittedly, their aesthetic appeal was part of the attraction, but they also offered intriguing insights.

I also experimented with Loom, which generated curious designs that added another layer of visual intrigue to the analysis.

The Reader tool was particularly helpful for identifying characters and their roles within each play. For example, in 1590’s Love’s Labour’s Lost, Reader listed characters like King Ferdinand of Navarre and Sir Nathaniel, giving me a quick snapshot of the dramatis personae. While this tool isn’t ideal for historical analysis, it’s excellent for literary reviews and understanding character dynamics.

One of the most practical features I learned was how to manage stop words—common words like “the,” “a,” “what,” and “so” that can clutter analysis. My first attempt at customizing stop words was a bit clumsy, leaving me with only the words I didn’t want. But once I enabled auto stop words for English, the tool worked seamlessly, refining my results and making the analysis more meaningful.

Using Voyant Tools to analyze Shakespeare’s plays gave me a deeper appreciation for textual patterns and stylistic evolution. It also sparked thoughts about authorship—especially in light of debates over whether Shakespeare was one man or a collective. Voyant allows us to deconstruct the plays and examine them through a digital lens, offering new perspectives on age-old questions.

This has been one of my favorite applications. While maps and spatial tools are invaluable in Digital History, textual analysis offers a different kind of vision—one that reveals the structure, rhythm, and nuance of literature. Voyant Tools bridges the gap between traditional literary study and modern digital exploration, making it an essential resource for scholars and students alike.

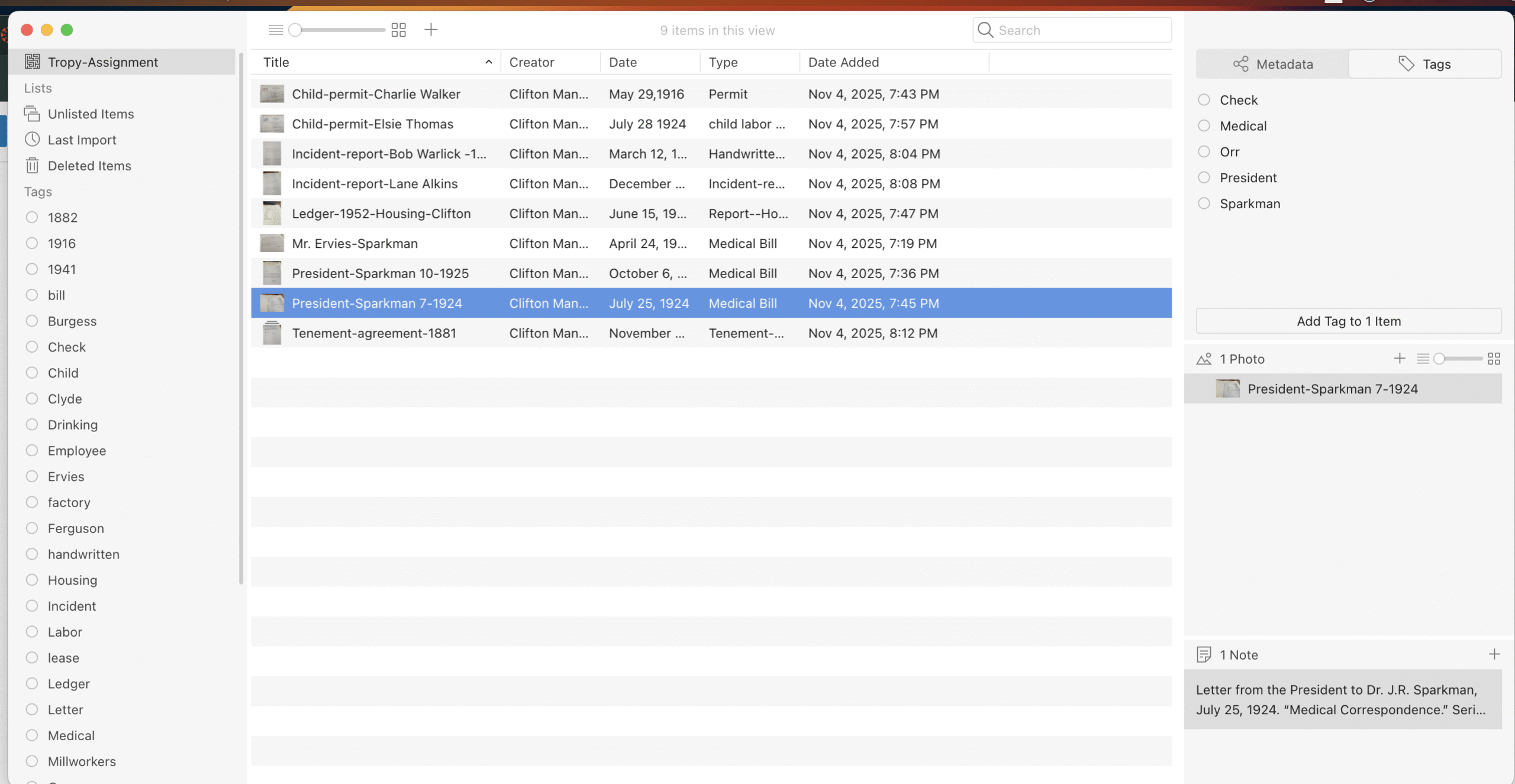

When I began my assignment with the Clemson University Archives, I had gathered a total of 371 photos. For the project, I only needed to work with ten sources, but the sheer volume of material made me realize how important it was to have a system for keeping everything straight. That’s where Tropy came in—not as a flashy new tool, but as a practical way to make sense of what I had collected.

I imported the ten sources I selected for the assignment into Tropy, and I could already see how it would be helpful for far more than just this exercise. Unlike Zotero, which I’ve never felt was useful, Tropy allows me to attach meaning directly to each photo. I could note why a particular image mattered, what it showed, and how it might connect to other pieces of evidence. That ability to combine organization with interpretation made the process feel less like filing and more like building the foundation of a story. The ease of entering the tags and metadata was clean and straightforward.

Two sets of documents stood out to me as I worked. The first were the child labor permits. For the assignment, I only entered two into Tropy, but in reality, I have hundreds. Most of the list children are between the ages of 12 and 14, which immediately raised questions about the legal framework that allowed this. In South Carolina, child labor was a significant issue in the textile industry. The state eventually passed laws restricting the employment of children under 14 in mills, though enforcement was uneven, and many families relied on children’s wages to survive. Seeing the permits, organized in Tropy, gave me a sense of the scale of this practice and the human stories behind the statistics. I will be able to put the names and ages of all the children and keep them organized under each child’s last name.

The second set of documents was the incident reports. These are handwritten and will take time to transcribe, but even at a glance, they reveal the texture of everyday life in the mill village. They record accidents, disputes, and small events that, when pieced together, create a vivid picture of the community. Having the names and events organized in Tropy means I can start to trace patterns—who was involved, what kinds of incidents were most common, and how the mill responded. I am entering names as tags so I can connect the individual to the incident.

Tropy didn’t just help me finish an assignment—it gave me a way to organize, contextualize, and interpret the hundreds of photos I brought back from the archive. And more importantly, it showed me how those photos can become evidence for telling the story of the mill village in all its complexity.

When I walked into Clemson Libraries’ Digitization Lab, I honestly thought digitization was simple. In my mind, it was just a big camera, a quick click, and done. Easy, right? Turns out, I couldn’t have been more wrong.

Before the lab visit, I went through Cornell’s https://www.library.cornell.edu/preservation/tutorial/ tutorial and watched the Library of Congress video https://www.loc.gov/preservation/digital/. Both made it clear that digitization isn’t just “taking a picture.” It’s about creating a digital copy that’s accurate enough to stand in for the original—color, detail, everything. That means resolution, lighting, calibration, and a whole lot of technical know-how.

Seeing it in person with Kelly Riddle, our Director of Digitization and Digital Projects, really drove it home. I was shocked at how long it takes to digitize even a simple page. And those cameras? They’re not just point-and-shoot. Kelly explained that the settings have to be recalibrated every single morning because even humidity can affect the sensitive lens. For projects like the National Park Service grant, there are strict https://planning.dc.gov/publication/nps-electronic-format-standards—and if those aren’t met, the image has to be redone. No shortcuts.

It made me think about my own work with metadata. For years, I’ve worked on metadata after the image is created—never during digitization. My experience started with historical Clemson photos, where I spent hours digging through Taps yearbooks to identify faces. Sometimes I’d find the exact photo, sometimes not. Later, I moved into cataloging rare and very old books, which is just as tedious in its own way. Metadata creation is slow, detailed work, and often involves building localized vocabularies for people and places as we identify them.

Right now, metadata and images live in separate worlds. The images are stored in numbered boxes, while metadata goes into CollectiveAccess. We match them by ID numbers, but they’re not bundled together. I’ve been told this workflow isn’t efficient—and I agree. We need a way to connect images and metadata into a single package. That would require new software capable of handling both. Clemson’s Collections Discovery department is actively working on new workflows, and there’s talk of a shared platform for Archives, Special Collections, and the Digitization Lab. At first, I thought that sounded overly complicated. Now, after seeing the digitization process up close, I understand why it’s necessary. A unified system would make collaboration smoother and ensure that the digital object and its metadata stay together.

What direction will this take us? I’m not sure yet. But I do know this: digitization isn’t fast, and it’s definitely not simple. It’s photography, metadata, compliance, and research—all working together. And I hope I get to work with historical images again. I miss that part a lot.

Walking out of the lab, I realized digitization isn’t just about creating access; it’s about creating trust in the digital record. And that trust takes time, skill, and a lot of patience. We made need to work to other technologies.

Child labor shaped the early textile industry in South Carolina, leaving behind stories that are hard to imagine today. To uncover these realities, researchers turn to archives—repositories of authentic voices and records that bring history to life.

One collection that stood out to me during my research was the Clifton Manufacturing Company Records (Mss-0136) at Clemson University Libraries Special Collections and Archives. Why this collection? Because it contains work permits for children, a rare and powerful window into the lives of young mill workers. Most permits are for 14-year-olds, but some, like the one for Charlie Walker at age 12, reveal how families and companies navigated the law—and sometimes bent it—to keep mills running.

By 1915, South Carolina passed a law requiring a signed statement from a parent or guardian affirming that a child was of legal employment age. This was meant to protect children, but in practice, it opened the door to abuse by desperate families seeking extra income.

Domestic and agricultural workers were exempt. Children over twelve with a widowed mother or disabled father were excused from age limits. Orphans could be employed at any age—one child reportedly began working at just five years old (South Carolina Encyclopedia).

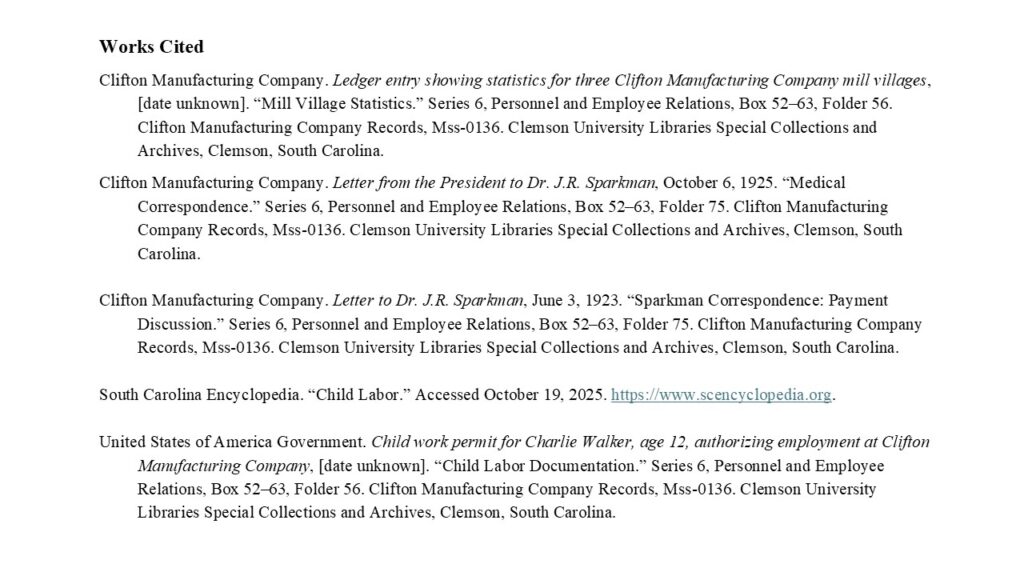

This context makes the child work permit for Charlie Walker, age 12, especially striking. Found in Series 6, Box 52–63, Folder 56, this U.S. government-issued permit authorized his employment at Clifton Manufacturing Company. It’s a tangible reminder of how legal frameworks were stretched to accommodate economic realities. For a future research project, this permit could serve as a focal point for studying enforcement gaps and family survival strategies during the Progressive Era.

Child labor wasn’t the only challenge in mill life—health care loomed large. Among the Clifton records are letters that reveal how medical issues were handled.

One letter, dated October 6, 1925, from the company president to Dr. J.R. Sparkman, discusses medical concerns for employees. Another, from June 3, 1923, addresses payment for medical services. Both are housed in Series 6, Box 52–63, Folder 75.

These letters suggest a complex relationship between mill owners and healthcare providers. They raise questions about corporate responsibility: Were mills genuinely concerned about worker welfare, or were these negotiations driven by economic necessity? A future research project could explore industrial health care practices and their role in shaping labor relations.

Numbers tell their own story. A ledger entry showing statistics for three mill villages, also in Series 6, Box 52–63, Folder 56, offers demographic and housing data. This single document could underpin a study of living conditions in mill communities—how family size, housing quality, and village layout influenced labor patterns and social life.

Combined with the work permits and correspondence, this ledger helps paint a fuller picture: mills weren’t just workplaces; they were ecosystems where economic, social, and health factors intertwined.

The Clifton Manufacturing collection is not fully curated. While the finding aid provides basic descriptions of series and folders, detailed item-level descriptions are missing. Researchers must rely on scope and content notes and series descriptions, then dig into boxes to uncover treasures like these permits and letters.

Together, these documents provide a multidimensional view of mill life—legal, medical, economic, and social. They are not just relics; they are reference points for future scholarship on labor history, public health, and industrialization in the South.

Archival research transforms abstract history into tangible narratives. By engaging with primary sources like those in the Clifton Manufacturing Company Records, we uncover the lived realities behind child labor statistics and legislation. These materials invite us to ask deeper questions—and perhaps, to tell stories that have long been silent.

In The Princeton Guide to Historical Research, Zachary Schrag emphasizes that verifying information is not just about confirming facts—it’s about understanding how sources are used to support historical arguments. This principle came into focus for me when I applied it to a close reading of Thomas Hudson Cartledge III’s 2019 master’s thesis, Recollections: Life in South Carolina Mill Villages.

I selected a two-page section from Cartledge’s thesis that discusses the role of children in mill village life, particularly their early entry into the workforce. Cartledge asserts that children as young as ten worked in spinning rooms and that this labor was normalized within mill communities. He cites oral histories from the WPA’s Federal Writers’ Project and census records to support these claims.

To verify his assertions, I located one of the WPA interviews he referenced, available through the Library of Congress’s American Life Histories collection. The interviewee, a former mill worker, recalled starting work at age ten and described the long hours and physical demands of spinning. I then cross-referenced this with the 1900 census, which listed her occupation as “spinner” at age twelve. These two sources aligned well, confirming Cartledge’s claim about the age and type of labor children performed.

However, not all citations were equally strong. Cartledge references a 1912 Congressional hearing on child labor, but the citation was vague. I tracked down the hearing transcript and found that while it did discuss Southern mills, it focused more on national policy debates than on firsthand accounts from South Carolina. This doesn’t invalidate Cartledge’s point, but it does show how a source can be used to bolster a narrative even if it only partially supports the claim.

This exercise reinforced Schrag’s point in Chapter 9 that historians must evaluate sources not just for what they say, but for how they’re used. Corroboration is key. Even seemingly objective sources like census records carry limitations—they don’t capture working conditions, family dynamics, or the emotional toll of child labor. That’s where oral histories become invaluable, offering context and nuance that raw data can’t provide.

Schrag also reminds us in Chapter 5 that the classification of a source depends on how it’s used. In this case, the WPA interview functioned as a primary source for understanding lived experience, while the census served as a supporting document. Together, they verified Cartledge’s assertions and deepened my understanding of how to use multiple types of evidence in tandem.

This process also echoes Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s call to rethink historical timelines and narratives in her essay “The Long Civil Rights Movement.” Hall encourages historians to challenge conventional periodization and to consider how memory and interpretation shape the stories we tell. Verifying information, then, is not just about accuracy—it’s about accountability to the past and to the people whose lives we study.

Works Cited:

Cartledge, Thomas Hudson, III. Recollections: Life in South Carolina Mill Villages. Master’s thesis, Clemson University, 2019. TigerPrints. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/3236/

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd. “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past.” The Journal of American History 91, no. 4 (2005): 1233–1263. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3660172.

Schrag, Zachary M. The Princeton Guide to Historical Research. Princeton University Press, 2021.

Library of Congress. American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936–1940. https://www.loc.gov/collections/federal-writers-project/about-this-collection/

FamilySearch. United States, Census, 1900. https://www.familysearch.org/en/search/collection/1325221

Wayne Flynt’s Dixie’s Forgotten People: The South’s Poor Whites offers a thoughtful and deeply researched look into a group that’s often been overlooked in Southern history. Rather than relying on stereotypes or generalizations, Flynt brings these communities to life with empathy, nuance, and historical insight.

After reading the book, I examined four scholarly reviews to gauge historians’ responses to Flynt’s work. Each reviewer brought a unique perspective—ranging from labor history to folklore, music, and gender studies—which helped me see the book in new and unexpected ways.

In this post, I’ll share how these historians interpreted Flynt’s study, compare their viewpoints, and reflect on what I learned from reading their critiques alongside the book itself. It’s a chance to see how historical scholarship becomes a conversation—one that’s rich, layered, and full of insight.

As I read through the four scholarly reviews of Dixie’s Forgotten People, I was struck by how each historian brought a different lens to Flynt’s work—almost like looking at the same landscape through four distinct windows.

James A. Hodges, writing in The Journal of Southern History, approaches the book from an economic and labor history angle. He appreciates Flynt’s detailed account of poor whites and their long-standing marginalization, especially in relation to New Deal labor policy. For Hodges, the book fills a gap in economic narratives that often overlook class divisions among white Southerners. He sees Flynt’s work as a much-needed correction to those broader historical oversights.

William B. McCarthy, on the other hand, takes a cultural route. In his review for The Journal of American Folklore, McCarthy focuses on Flynt’s ethnographic storytelling—his attention to folk traditions, oral histories, and cultural practices. He praises the book for affirming the uniqueness of Southern cultural narratives and sees poor whites not just as economically disadvantaged, but as keepers of rich and meaningful traditions. Where Hodges is drawn to policy and structure, McCarthy is captivated by memory and storytelling.

Bill C. Malone, writing in The Journal of American History, finds a middle ground between social and cultural history. Known for his work on Southern music and working-class identity, Malone highlights Flynt’s ability to connect historical analysis with artistic insight. He describes the book as accessible and relevant, particularly for readers interested in the intersection of class and culture. Like McCarthy, Malone values Flynt’s attention to everyday life, but he’s especially attuned to how music and labor shape identity.

Margaret Ripley Wolfe, in The North Carolina Historical Review, brings yet another layer to the conversation: gender. She applauds Flynt’s portrayal of Southern women and families, noting how the book sheds light on domestic life and the roles women played in sustaining poor white communities. Wolfe’s review adds depth by emphasizing the social fabric of the South and Flynt’s contribution to a more inclusive historical narrative.

Together, these reviews demonstrate the multifaceted nature of Flynt’s book. Hodges sees structural inequality, McCarthy sees cultural preservation, Malone sees class identity through music, and Wolfe sees the strength of family and gender roles. None of them contradict each other—instead, they build on one another, offering a richer, more layered understanding of the South’s poor whites.

In the early 20th century, it wasn’t uncommon to find children as young as ten working long hours in South Carolina’s textile mills. Their small hands and quick reflexes made them ideal for tasks like mending threads or cleaning machinery — but the reality behind those jobs was far from ideal. This chapter of labor history reveals how industrialization reshaped childhood, family roles, and entire communities.

Mill Owners and Economic Justification

Lewis W. Parker, a prominent South Carolina mill owner, testified before Congress in 1914 to defend the practice. He claimed that some children earned more than their fathers, framing child labor as a financial necessity for struggling families. To Parker, children were simply better suited to mill work — a practical solution to poverty, not a moral dilemma.

Reformers and the Power of Photography

In stark contrast, photographer Lewis Hine captured haunting images of child workers for the National Child Labor Committee. His photos, often labeled with names, ages, and job descriptions, were designed to stir public outrage. Hine’s work helped fuel the push for reform by highlighting the human cost of industrial progress.

Everyday Life in the Mill Villages

The book Like a Family: The Making of a Southern Cotton Mill World offers a more nuanced view. Drawing from oral histories and archival research, it shows how child labor was woven into the fabric of mill village life. Families often relied on every member — including children — to make ends meet. The tone is empathetic, showing how economic hardship and cultural norms sustained the system.

This history isn’t just about labor laws or factory conditions — it’s about how childhood itself was redefined. In many mill families, work blurred the lines between child and adult. As one chapter of my thesis puts it:

“In South Carolina’s textile mills, children as young as ten routinely worked twelve-hour shifts, their small hands and quick reflexes prized by manufacturers. For many families, child labor was not a choice but a necessity — one that blurred the boundaries between childhood and adulthood.” Understanding these stories helps us see how industrialization shaped not just economies, but lives — especially the lives of the youngest workers.

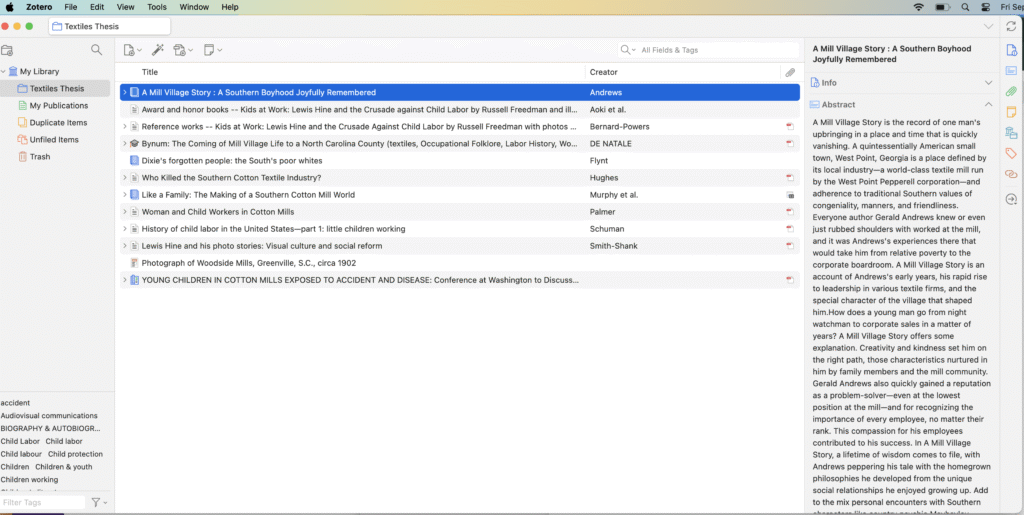

As a Library Specialist and a graduate student working on a thesis about South Carolina’s textile industry and its impact on children between 1877 and 1921, I’ve recently revisited Zotero—and I’m glad I did.

Zotero’s ability to pull citation information directly from websites, databases, and even my library’s catalog has saved me hours of manual entry. In many cases, it even retrieved the full-text PDF of the article and attached it to the citation record—an unexpected but very welcome feature.

For my first round of experimentation, I gathered 12 secondary sources from a variety of platforms: JSTOR, Project MUSE, ProQuest, Internet Archive, Google Scholar, and the Clemson University Library catalog. I intentionally mixed formats—books, journal articles, a photo, and even a thesis I’m using for inspiration. Zotero handled all of them seamlessly.

Beyond Bibliographies: Notes and Organization

While Zotero’s automatic citation generation is impressive, my favorite feature is the note field. I use it to record how I plan to use each source, highlight relevant pages, and jot down ideas. Although Zotero allows you to underline passages within PDFs, I find the notes more helpful for organizing my thoughts and tracking the purpose of each source.

How Zotero Is Helping Shape My Thesis

One key insight I’ve noted is that the Great Depression began affecting the South much earlier than the 1929 stock market crash—some sources suggest as early as 1921. This economic hardship deeply impacted textile mill communities, and I’m especially interested in how children adapted to these cultural and labor shifts.

Final Thoughts

If you’re working on an extensive research project, I highly recommend Zotero. It’s user-friendly, powerful, and adaptable. Whether you’re writing a thesis, organizing archival materials, or just keeping track of your reading, Zotero can streamline your workflow and help you stay focused on what matters most: your ideas.