Experimenting with Transkribus: Handwriting Recognition in Historical Research

For this final research exercise, I had the chance to experiment with Transkribus, an AI-powered handwriting recognition tool designed to help scholars work with manuscript materials. I approached the platform with a mix of curiosity and skepticism, since most of my archival work involves handwritten incident reports and permits from mill towns in the American South. These documents are often written in highly stylized cursive, which can be difficult to decipher even for trained eyes.

The setup process was straightforward. After creating an account and selecting “Academic Research,” “Just Me,” and “A Small Collection,” I named my project and entered the workspace Transkribus calls “My Desk.” The interface was clean and intuitive, and I appreciated that the tutorials were short and accessible. Within minutes, I was uploading sample documents and testing the recognition features.

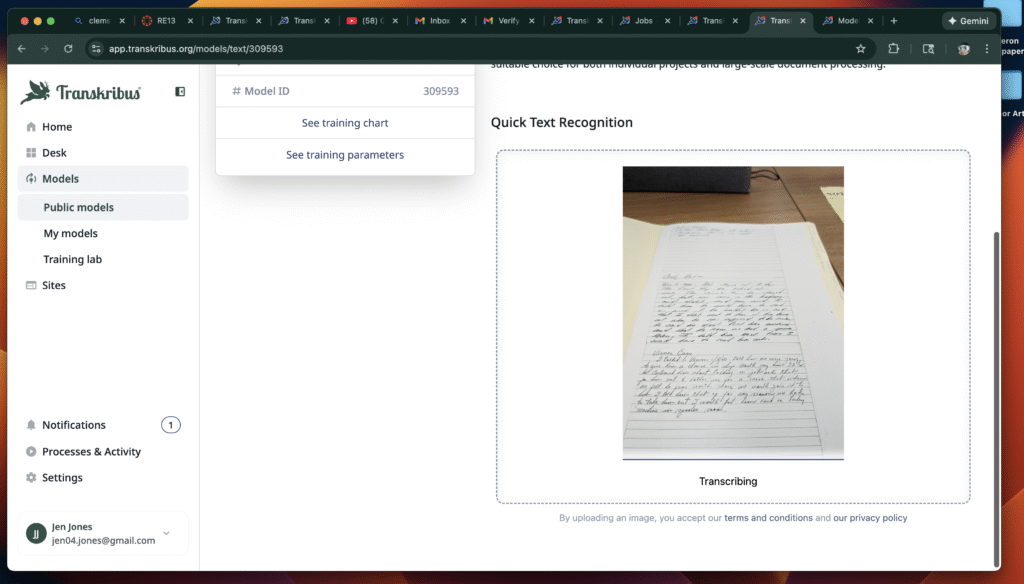

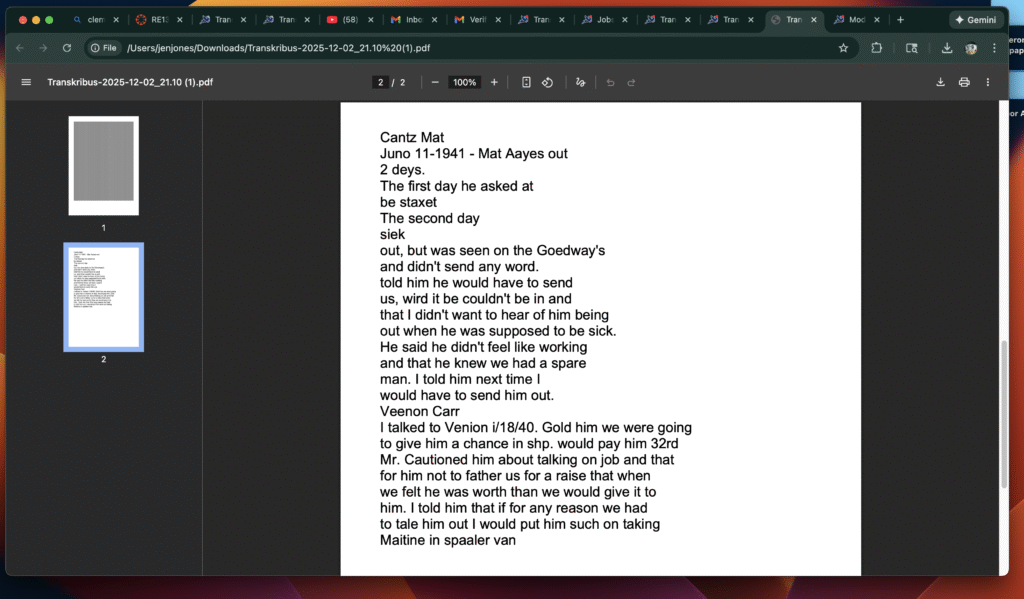

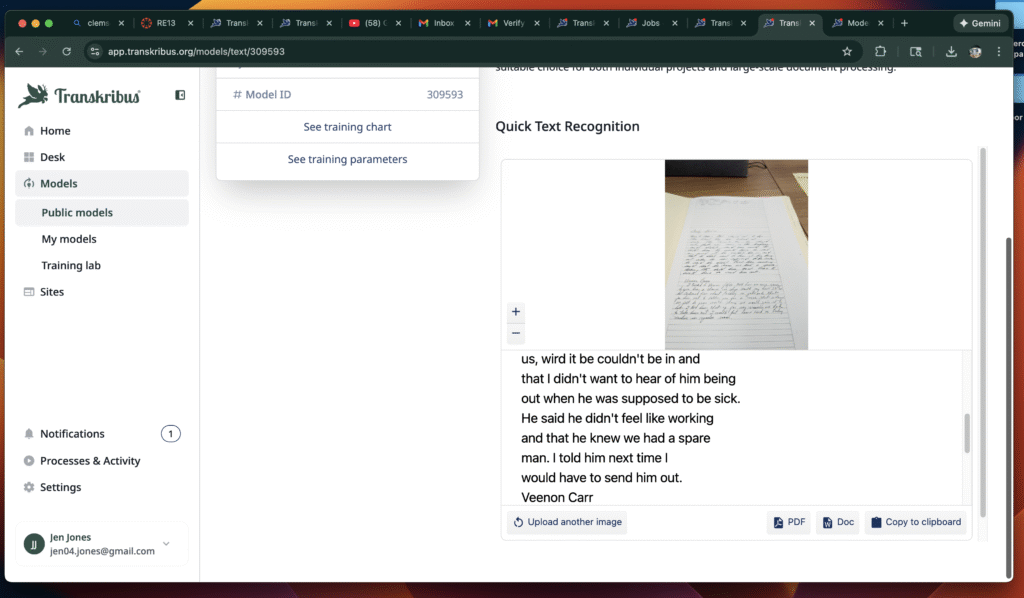

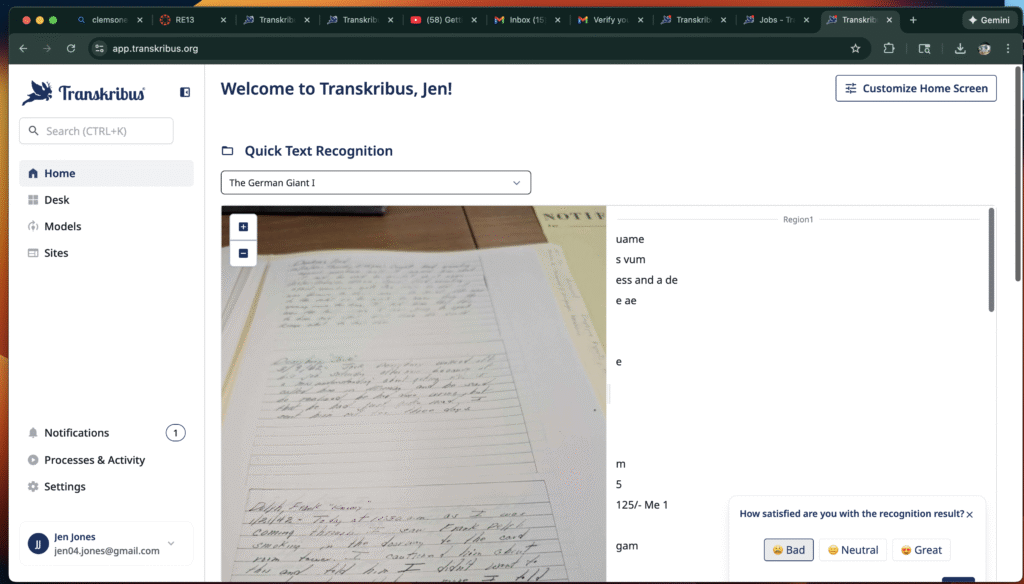

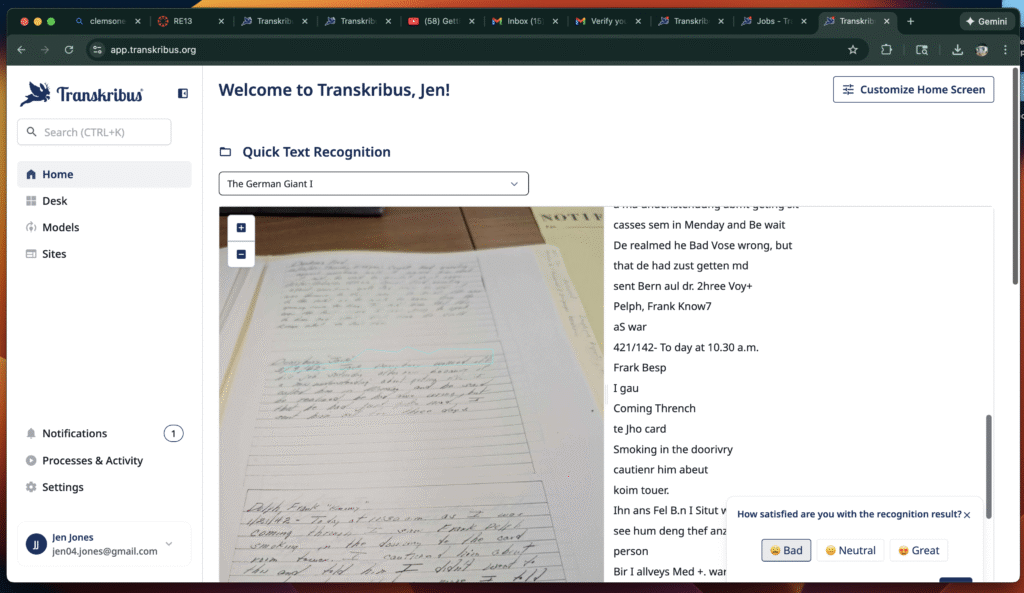

One of my first observations was that the software performed much better with typed or printed materials than with handwritten ones. When I uploaded a printed page, the transcription was nearly flawless, and the tool neatly separated the text into manageable sections. This alone is useful, since it makes digitized documents easier to read and annotate. However, when I tried the handwritten incident reports from Clifford Mill, the results were more uneven. The AI struggled with the flourishes and idiosyncrasies of the cursive script, often misreading words or leaving gaps.

That said, I can see enormous potential here. Transkribus allows users to train models on specific handwriting styles, meaning that with enough input, the system could eventually learn to recognize the quirks of the mill reports. Since I have pages and pages of these incident records, I could build a custom model over time. This would not only save me hours of manual transcription but also open up new possibilities for analysis. For example, once transcribed, the reports could be searched for recurring themes—such as the kinds of behaviors that were praised or condemned in mill communities. This would give a more vivid picture of everyday life, especially the tensions between workers and management.

Another feature I found helpful was the way Transkribus split documents into sections, making them easier to navigate. Even when the handwriting recognition was imperfect, the segmentation helped me focus on smaller portions of text. I also experimented with uploading screenshots of both printed and handwritten materials, which gave me a clear sense of the tool’s strengths and limitations.

At this stage, my collection is relatively small—approximately 5,000 words—but the platform’s scalability is encouraging. I can imagine expanding this into a larger project, where the AI gradually improves as it encounters more examples of the same handwriting. The idea of “training” the tool feels collaborative, almost like teaching a research assistant to recognize a particular scribe’s style.

In conclusion, while Transkribus is not yet a perfect solution for my handwritten mill reports, it is a simple, accessible, and promising tool. With time and training, it could become an indispensable part of my workflow, helping me unlock the voices hidden in these difficult manuscripts. For historians working with challenging handwriting, this tool offers a glimpse of how AI might transform archival research—making the past not only more legible but also more searchable and analyzable.