Exploring Shakespeare with Voyant Tools: A Visual Journey into Textual Analysis

In my class, we have explored new tools, which was one of the most eye-opening experiences I’ve encountered. There are ways to create digital history without needing to be a coder. One of the most useful tools I’ve encountered is Voyant Tools—a web-based application for performing textual analysis on large corpora. For this class today, I explored Shakespeare’s plays using Voyant, and I quickly discovered how powerful and visually compelling this platform can be. For this exploration, I used the plays of Shakespeare.

Shakespeare Visuals

Voyant Tools offers a preloaded corpus of Shakespeare’s plays, which can be accessed by clicking “Open” below the “Add texts” box. This corpus includes 895,737 words from 37 plays written between 1590–1613. You can also upload your own texts or use input boxes and URL links to compile texts from websites. The platform supports a wide range of file types—MS Word, Excel, HTML, RTF, PDF, XML, and Plain Text—making it incredibly flexible and user-friendly for researchers of all levels.

Visual Tools: Knots and Bubbles

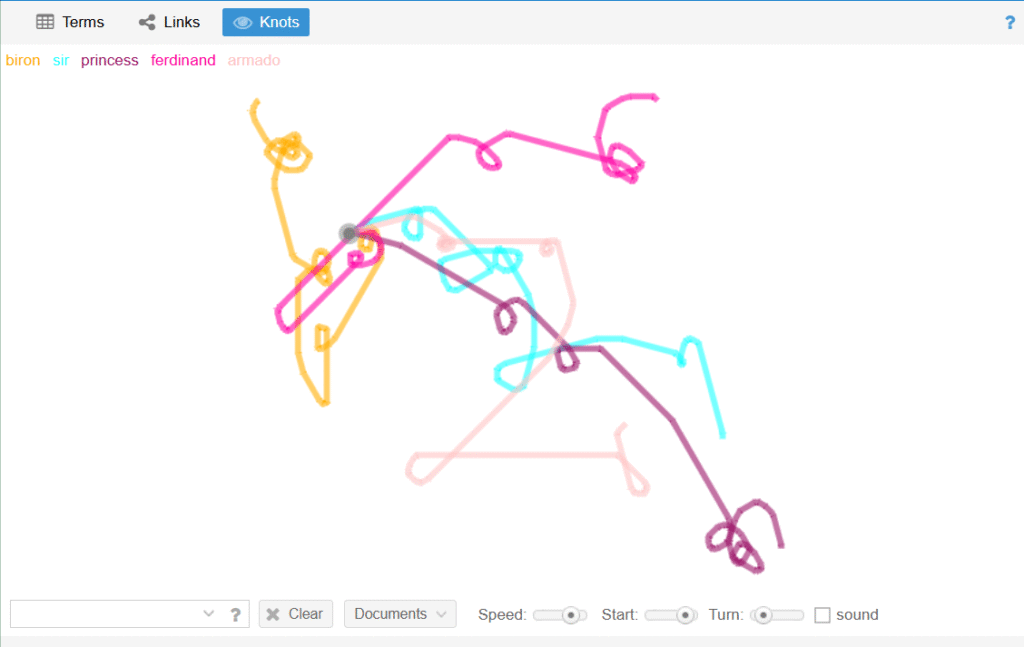

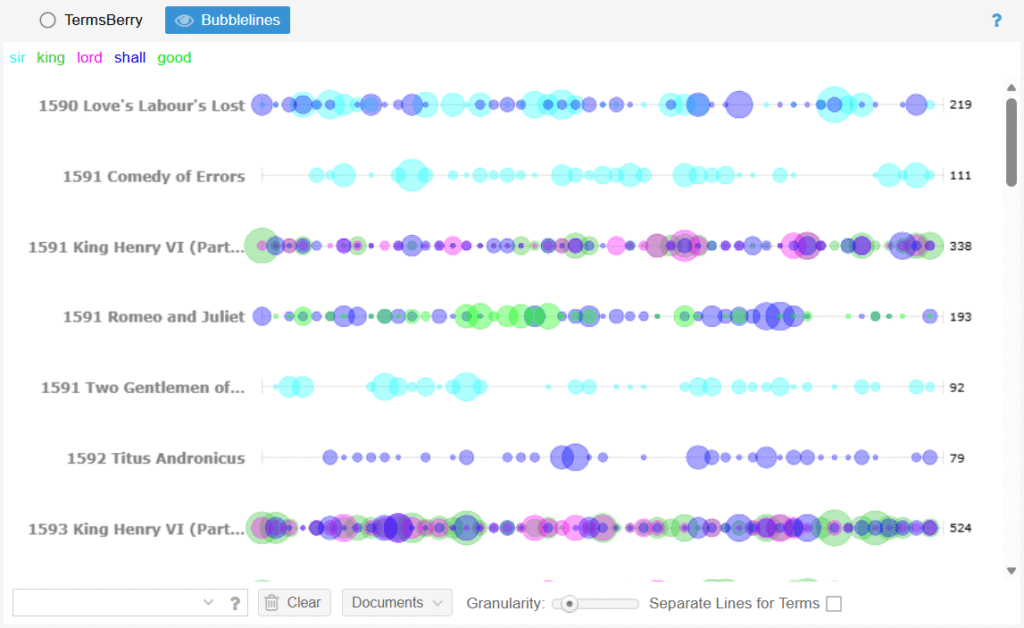

I was immediately drawn to two visual tools: Knots and Bubbles. Admittedly, their aesthetic appeal was part of the attraction, but they also offered intriguing insights.

- Knots creates a web of connections between words, but I found it challenging to interpret its deeper meaning. It looked fascinating, yet I struggled to extract concrete insights from it.

- Bubbles, on the other hand, was more intuitive. It allowed me to compare plays across time, revealing patterns in Shakespeare’s writing. For instance, the visual similarities between 1591’s Comedy of Errors and 1593’s Two Gentlemen of Verona made sense—they’re essentially the same play, and the tool reflected that beautifully. The size and color variations in the bubbles helped highlight thematic and stylistic shifts over the years.

I also experimented with Loom, which generated curious designs that added another layer of visual intrigue to the analysis.

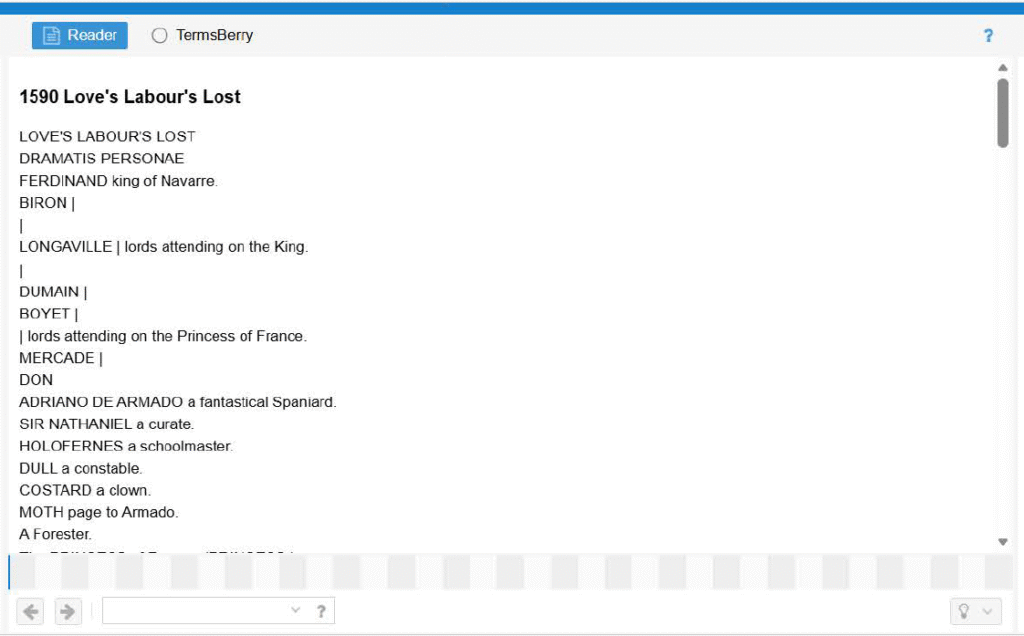

Textual Tool: Reader

The Reader tool was particularly helpful for identifying characters and their roles within each play. For example, in 1590’s Love’s Labour’s Lost, Reader listed characters like King Ferdinand of Navarre and Sir Nathaniel, giving me a quick snapshot of the dramatis personae. While this tool isn’t ideal for historical analysis, it’s excellent for literary reviews and understanding character dynamics.

Customizing with Stop Words

One of the most practical features I learned was how to manage stop words—common words like “the,” “a,” “what,” and “so” that can clutter analysis. My first attempt at customizing stop words was a bit clumsy, leaving me with only the words I didn’t want. But once I enabled auto stop words for English, the tool worked seamlessly, refining my results and making the analysis more meaningful.

What I Learned

Using Voyant Tools to analyze Shakespeare’s plays gave me a deeper appreciation for textual patterns and stylistic evolution. It also sparked thoughts about authorship—especially in light of debates over whether Shakespeare was one man or a collective. Voyant allows us to deconstruct the plays and examine them through a digital lens, offering new perspectives on age-old questions.

Final Thoughts

This has been one of my favorite applications. While maps and spatial tools are invaluable in Digital History, textual analysis offers a different kind of vision—one that reveals the structure, rhythm, and nuance of literature. Voyant Tools bridges the gap between traditional literary study and modern digital exploration, making it an essential resource for scholars and students alike.