Meridian of choices

What is life, if not a meridian of choices?

Zachary Schrag, who wrote in The Princeton Guide to Historical Research, reminds us that history is shaped by the decisions people make. Whether as individuals or as part of a group, they face specific circumstances. It’s a simple idea, but one that carries profound weight. At its core, history is about the choices we make.

Other disciplines have their own focus. Geologists study the land and water. Archaeologists sift through material remains. Epidemiologists track the spread of disease. But historians? Historians ask why. Why did people respond the way they did? What motivated their actions? What shaped their decisions? Who were they?

My research focuses on textile workers and their families. Ordinary people navigating lives shaped by forces beyond their control, yet still making meaningful choices within those constraints. I used to think that psychology would help me understand the human mind, but I’ve found that history, with all its complex layers and moral nuances, offers even more profound insight.

Schrag’s examples of tobacco and chocolate illustrate this beautifully. Why did early Europeans choose to transform chocolate into a bitter drink and cultivate tobacco as an ornamental plant? These were cultural choices, influenced by taste, trade, and imagination. At every moment in history, the paths people chose reveal something essential about who they were and how they perceived the world.

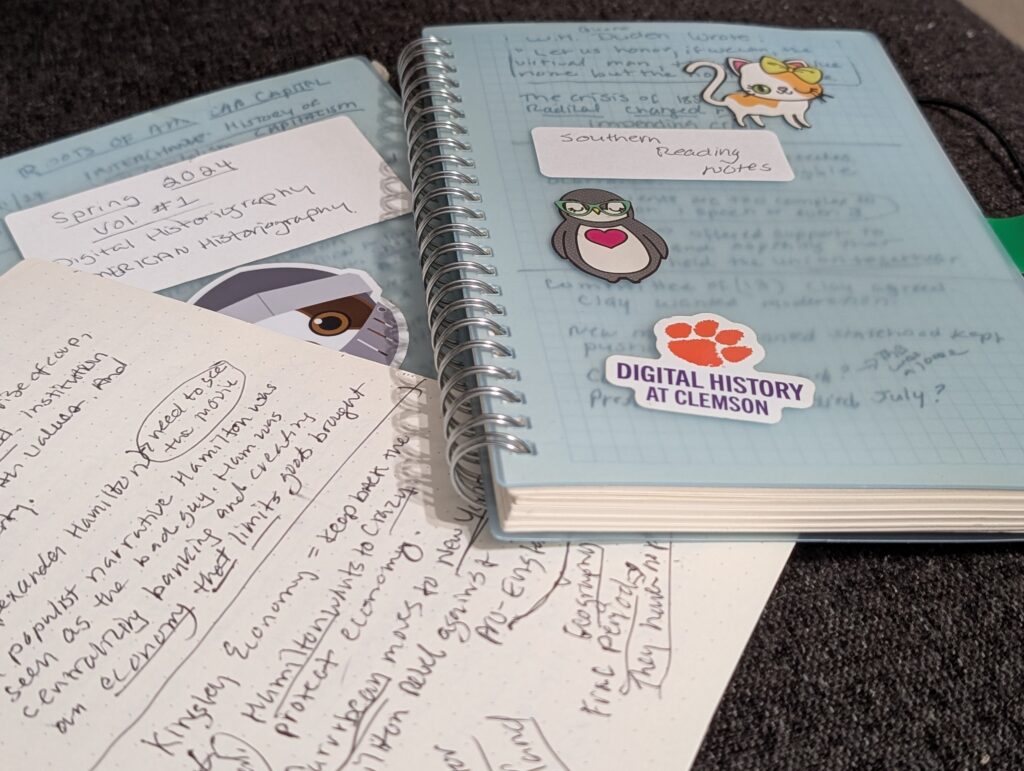

Historians are note-takers, archivists, and accidental comedians. I’ve followed the old style of using notebooks the size of notecards for my research notes. However, I learned from the reading that I need to improve my habits. I need to organize my notes by time, theme, or other system. I have notebook upon notebook, but I have only put them under class name, date, and within the notes, the title of a book. This is fine for a class paper, but for my thesis, I won’t be able to find essential resources. While I do cling to the written word, I need to begin using technology. I am considering creating a spreadsheet for my notes that can be sorted by theme, date entered, and source citation.

And we record surprises, like the time a rooster disrupted a town council meeting by crowing every time someone mentioned the word “budget.” That’s not just a funny story. That’s gold dust.

No one person has all the control; as human beings, there are always external factors, circumstances, and other people that bring about change. This is why, at first, simply stating that History is about choices seemed too simplistic. Numerous factors influence the decisions made. Nothing is inevitable.

History is the study of choices—but not just the ones made freely. It’s the study of constrained decisions, of reactions to change, of people trying to make sense of their world. And in that sense, historians aren’t just keepers of the past, but interpreters for the most chaotic and compelling of topics, humanity.