Verifying Information in Historical Research

Primary Sources in Context

In The Princeton Guide to Historical Research, Zachary Schrag emphasizes that verifying information is not just about confirming facts—it’s about understanding how sources are used to support historical arguments. This principle came into focus for me when I applied it to a close reading of Thomas Hudson Cartledge III’s 2019 master’s thesis, Recollections: Life in South Carolina Mill Villages.

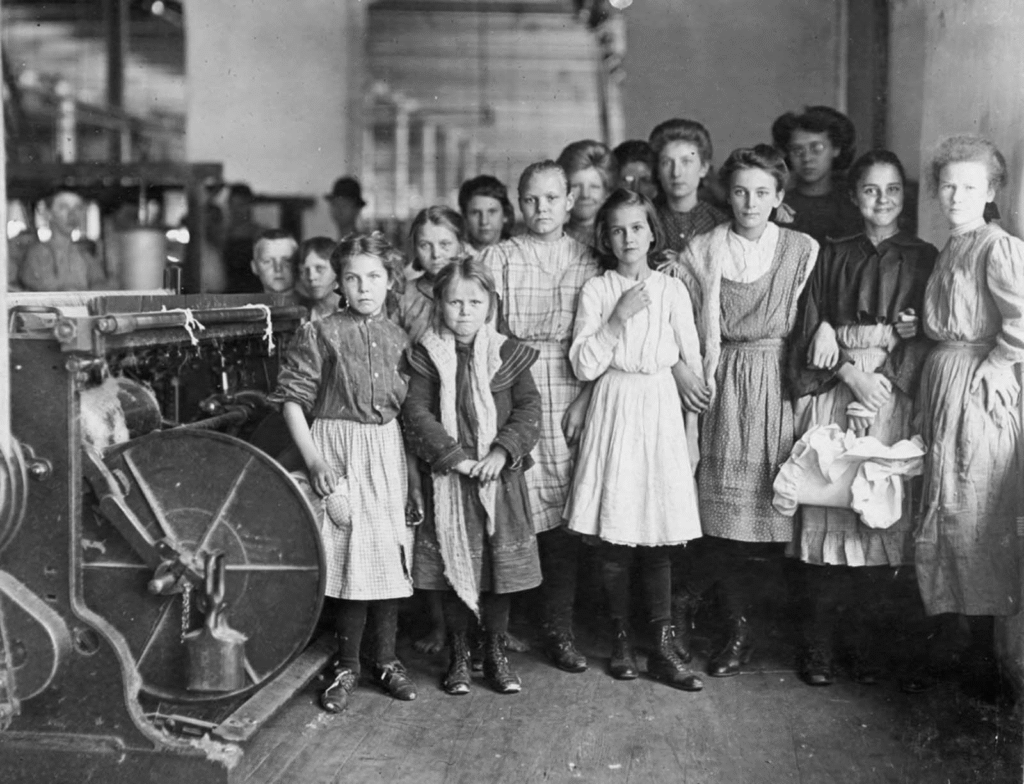

I selected a two-page section from Cartledge’s thesis that discusses the role of children in mill village life, particularly their early entry into the workforce. Cartledge asserts that children as young as ten worked in spinning rooms and that this labor was normalized within mill communities. He cites oral histories from the WPA’s Federal Writers’ Project and census records to support these claims.

To verify his assertions, I located one of the WPA interviews he referenced, available through the Library of Congress’s American Life Histories collection. The interviewee, a former mill worker, recalled starting work at age ten and described the long hours and physical demands of spinning. I then cross-referenced this with the 1900 census, which listed her occupation as “spinner” at age twelve. These two sources aligned well, confirming Cartledge’s claim about the age and type of labor children performed.

However, not all citations were equally strong. Cartledge references a 1912 Congressional hearing on child labor, but the citation was vague. I tracked down the hearing transcript and found that while it did discuss Southern mills, it focused more on national policy debates than on firsthand accounts from South Carolina. This doesn’t invalidate Cartledge’s point, but it does show how a source can be used to bolster a narrative even if it only partially supports the claim.

This exercise reinforced Schrag’s point in Chapter 9 that historians must evaluate sources not just for what they say, but for how they’re used. Corroboration is key. Even seemingly objective sources like census records carry limitations—they don’t capture working conditions, family dynamics, or the emotional toll of child labor. That’s where oral histories become invaluable, offering context and nuance that raw data can’t provide.

Schrag also reminds us in Chapter 5 that the classification of a source depends on how it’s used. In this case, the WPA interview functioned as a primary source for understanding lived experience, while the census served as a supporting document. Together, they verified Cartledge’s assertions and deepened my understanding of how to use multiple types of evidence in tandem.

This process also echoes Jacquelyn Dowd Hall’s call to rethink historical timelines and narratives in her essay “The Long Civil Rights Movement.” Hall encourages historians to challenge conventional periodization and to consider how memory and interpretation shape the stories we tell. Verifying information, then, is not just about accuracy—it’s about accountability to the past and to the people whose lives we study.

Works Cited:

Cartledge, Thomas Hudson, III. Recollections: Life in South Carolina Mill Villages. Master’s thesis, Clemson University, 2019. TigerPrints. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/3236/

Hall, Jacquelyn Dowd. “The Long Civil Rights Movement and the Political Uses of the Past.” The Journal of American History 91, no. 4 (2005): 1233–1263. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3660172.

Schrag, Zachary M. The Princeton Guide to Historical Research. Princeton University Press, 2021.

Library of Congress. American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936–1940. https://www.loc.gov/collections/federal-writers-project/about-this-collection/

FamilySearch. United States, Census, 1900. https://www.familysearch.org/en/search/collection/1325221